In most English societies, for centuries Christmas has been a time of gatherings, and food, and festivities, and traditions, and family. For many people in the eighteenth century, Christmas was celebrated much differently than it typically is today. Remnants of the old holiday customs can still be found in rhyme and song. “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” for instance, is a whimsical 18th century English carol that enumerates the progressive celebrations starting with Christmas day and culminating with Epiphany.

Christmas was Incomplete without Christmas Pie…but Which One?

There were traditional celebrations along with their traditional foods. One such dish was the Christmas pie. Now there were apparently two kinds of Christmas pies known to the English: the Yorkshire pie, and the mince pie.

The Yorkshire pie was nearly always made using a large standing crust. It was filled with a series of progressively larger fowl, boned and wrapped around the smaller fowl. A pigeon, for instance, might be boned and wrapped around a piece of forcemeat or sausage. A game hen would then be boned and wrapped around the pigeon; a chicken, the same, and wrapped around the game hen; a duck around the chicken; a goose around the duck; a turkey around the goose, and then maybe a swan around the turkey. The result would be a grand dish that when sliced would offer a variety of tasty meats spectacularly arranged in concentric circles. The standing-crust pie adorned with a swan’s head and wings in the above David Tenier the Younger’s painting, could very well be a Yorkshire style pie.

The French culinary artist, Grimod de La Reynière, apparently found fame through a recipe in his 1807 book, “Almanach des Gourmands,” that utilized no less than 16 different birds, each boned and wrapped around the smaller: a turkey, a goose, a pheasant, a chicken, a duck, a guinea fowl, a teal, a woodcock, a partridge, a plover, a lapwing, a quail, a thrush, a lark, an ortolan bunting, and a garden warbler.

So, the “turducken” really isn’t all that novel an idea after all.

The other type of Christmas pie that I’m focusing on in this post is the traditional mince pie. Mince pies are thought to have been good English fare since the return of the crusaders. The earliest recipes appear to date back to the 15th and 16th centuries. The earliest versions were strickly meat pies, but by the 18th century, sweeter meatless varieties were well accepted. And by then, both the meaty and meatless versions were tightly associated with Christmas.

From The Lady’s Magazine, 1780Finding and Duplicating the Perfect Mince Pie

In my research, I found three dozen 18th and early 19th century recipes for mince pie from 24 different sources (before I decided enough was enough). As I compared the recipes, I couldn’t resist musing on the fallacy of accuracy when it comes to interpreting 18th century recipes. I shared my thoughts in an earlier post. The fact is, none of the recipes I found are precise enough to dispel a shadow of a doubt that we have duplicated them exactly. Virtually all of the recipes left one factor or another up to the taste of the cook. I’ll not say any more about that, you can read the post if you wish. I suppose finding that perfect recipe is a fallacy as well, given that so much depends on personal taste.

Observations on the Mince Pie Recipes:

Meat or No Meat?

First things first, regarding the use of meat: two-thirds of the recipes I found included meat as an ingredient, while 1/3 third were meatless. Meats with fine grains were preferred. Ox tongue and beef from the “inside of the sirloin” (what is now referred to as the tenderloin) are choice.

Sweetmeats:

Currants were the most frequently mentioned of the sweetmeats over the spectrum of recipes (mentioned 32 times). I’m not talking about the red or black gooseberry cousins with which we like to make jams and jellies. I’m talking about what we Americans call “Zante” currants. This variety of currant is a small dried seedless Corinth grape — a mini-raisin.

Depending on how well your local grocery store shelves are stocked, currants can sometimes be a challenge to find. They can sometimes be found next to the raisins in your grocery store. Other times, they’ll be located next to the fruitcake supplies during the holiday season.

This seedless feature of the Corinth grape was most appreciated by 18th century cooks, I’m sure. Raisins of the 18th century apparently were not like our modern seedless cultivars. They had to be “stoned” before one could use them in cooking — that is, the seeds had to be removed. Stoning four pounds of raisins, for instance, would have been a tedious and sticky job, whereas, the only preparation needed for currants was to make sure they were clear of stems, washed, and well dried.

So if you can’t find currants in your local store, raisins are a suitable seedless substitute. And while you’re looking for currants among the fruitcake supplies, be sure to pick up a few containers of candied orange rind, candied lemon rind, and for you die-hard fruitcake fans, candied citron rind. These sweetmeats were mentioned 23, 12, and 22 times in the recipes, respectively.

In case your wondering, a citron is a bitter, juice-less cousin to our edible citrus fruits.

Fresh Lemon rind was also fairly common, with 16 recipes calling for it.

Sugar:

32 of the 36 recipes used sugar of some kind — either powdered sugar, cone sugar (white sugar), or “wet sugar” (brown sugar). The proportion by which it was used varied tremendously.

Apples:

Apples are our next most common ingredient. Of the 36 recipes, apples were included as ingredients 31 times. A few of the recipes suggested the tartest apples you could find. Others recommended “good baking apples.”

Seasonings:

The two most commonly used spices in the old mince pie recipes were nutmeg and its aril companion, mace — both mentioned 25 times. Ground clove was mentioned 23 times, but it was usually used in lesser quantity than nutmeg or mace. Cinnamon was mentioned in 19 recipes, and when it was, it was often used in greater quantity than nutmeg and mace. Salt was used surprisingly in only 16 of the recipes.

Liquids:

In order of the number of mentions: wine (32 mentions)– either fortified (i.e., sack, port, and “mountain wine”) or unfortified (e.g., white, red, claret or Bordeaux), brandy (27 mentions), Lemon Juice (15 mentions), Orange juice (7), Ver Jus (2).

If you prefer to not use alcohol in your mince pie, one recipe suggested using beef broth, and another, cider. One thing you may wish to consider, however, is that alcohol helped preserve mince. Mince was often made in large batches and stored for months prior to use. Batches of mince that omit alcohol should be used immediately.

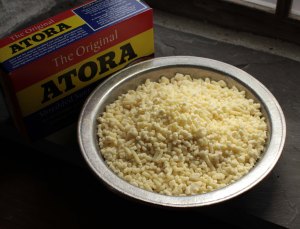

Ah, the Secret Ingredient: SUET!

In all but two of the recipes, suet is listed as a major ingredient. It was the most frequently mentioned of all the other ingredients. Suet is the hard fat found surrounding the kidneys in beef and mutton. It is a milder tasting fat that normal beef and mutton fat, and it has a higher melting point. These two features make it an important factor in many successful English dishes, including mince pie.

Suet adds moisture to the pie. In addition, the higher melting point allows surrounding ingredients to set before the suet melts. This gives the final dish a light and airy texture. This textural effect is even more pronounced in English puddings.

The proportional use of suet varies greatly among the 36 recipes. In the English Art of Cookery (Briggs, 1788), suet accounts for nearly half of the total quantity of ingredients. Most recipes use it in much smaller proportions.

The problem with suet, however, is that unless you live in Great Britain, or your uncle Harry owns a butcher shop, suet can be really hard to find. If you have managed to endear your local butcher, he or she may be able to reserve suet for you. But even if you do have access to raw suet, preparing it for use can be quite challenging. You can buy pre-shredded food-grade suet on-line from our British friends.

A modern alternative to suet, though admittedly it is inferior to the original, is vegetable shortening. Vegetable shortening has a melting point that falls within the range of that of suet. While it’s flavor is similarly mild to suet, vegetable shortening’s texture, however, is different. Whereas suet can be shredded pretty much at room temperature, vegetable shortening must be frozen first. From experience, if you are going to substitute shortening for suet, I suggest you reduce the amount called for in the recipe by at least half, otherwise, you’ll be pouring off extra melted vegetable shortening from your pie upon removing it from the oven.

Which Crust should be used?

In an earlier post, I explained three basic categories of crusts used in the 18th century: the standing crust, the puff paste, and the short paste. All three are acceptable for mince pies, though a large standing crust or a puff pastry is most often mentioned in the original recipes.

Preparing Mincemeat in Advance

It’s likely that most mince recipes were intended to be made in advance. Specific suggestions are given in a number of the recipes to ensure longer storage life.

Certain ingredients have a tendency to spoil. Some recipes suggest leaving out the apples and suet until the mince is to be used. Others suggest the meat should also be a last-minute addition. There is fairly clear consensus that candied orange rind should be added as needed and not included in the recipe during long-term storage. Orange rind, as opposed to lemon rind, apparently has the tendency to impart over time a bitter taste to the mince.

A basic technique for potting mince for later use is to pack it well into a stoneware pickling jar or storage crock, making sure no air is trapped in the mince. Next, cut a circle from a piece of paper (e.g., writing paper is fine) that will fit nicely over the surface of your mince. Next, pour about a cup of brandy over the paper. This can then be sealed off with a bladder and a piece of paper tied over the mouth of the jar. With proper preparation and storage in a cool place, a number of recipes claimed the mince would keep for six months to a full year. One recipe suggests mince only gets better given a chance to age in storage for a while. If you pot your mince, be sure to mix the pot well before using it, as many of the best flavors will settle in the bottom of the pot.

Not Just for the British

Modern regional traditions suggest mince was a common fare among many American colonists. The early 19th century American cookbook The Virginia Housewife, by Mary Randolph (1838, p. 115) supports this hypothesis.

By the way, the aforementioned Yorkshire Christmas pie can likewise be found in The Carolina Housewife, by Sarah Rutledge (1847, p. 85).

A Selection of Recipes:

In our video, we’ve adapted the meatless recipe below by Elizabeth Raffald, adjusting the amounts to make two 9″ mince pies. We substituted vegetable shortening for suet (and reduced its proportion), and omitted the citron altogether.

From The Experienced English Housekeeper, by Elizabeth Raffald (1769, p. 133):

From Cookery and Pastry, by Susanna MacIver (1773, p.111):

From The Compleat Housewife, by Eliza Smith, (1727, p. 138):

From The Practice of Cookery, by Mrs. Frazer (1781, p. 171):

From The Lady’s Assistant, by Charlotte Mason (1775, p. 389):

From The Frugal Housewife, by Susanna Carter (1788, p. 80):

Pingback: Suet, Part two: What it is, What it isn’t, and What to Look For. | Savoring the Past

Apparently, the apple don’t fall far from the tree… This was an enchanting segment. Thanks.

Pingback: Suet, Part Four: A Few Recipes. | Savoring the Past

Dad, all I can say is that little one has the cutest smile and Lord the devil in her eyes. She reminds me of my 2 little blonds, only they are not so little any more, now I have grand daughters to teach.

Thanks

I used an Alaskan Ulu knife to mince my raisins, that seemed to do a better job than my puny hand-cranked food processor. (And the design would be period correct, just not geographically correct, in most cases.).

To clarify: if using Suet, you’d use twice as much suet as vegetable shortening, right? I divided the quantities in the video by four to experiment, and came out with 6oz raisins, 4oz apples, 1oz Orange peel, and 5oz suet. This is a little less than 1/3 the total quantity of ingredients. You said some recipes used as much as half the total quantity, but most “much smaller proportions”… Is this 1/3 by weight within the typical range? When mixed it looks like a lot. Visually it looks like a lot more than what Jon and Ivy had in their mixing bowl, but part of it, I expect, is that my suet keeps its white color better than their shortening.

I’m making tarts in ramekins to start with, eager to see how they come out.

Thanks very much for your great work!

Pingback: Yorkshire Christmas Pie | countryhousereader

I liked my results. The first batch of four tarts seemed to have a little much fat, so I added more raisins for the second batch. Next time I will use four oz of suet on the quarter recipe. The second batch yielded three more tarts, so I got seven out of my small batch. My dad and father-in-law (the only other mincemeat eaters in my family) both approved.

The little girl is a true heart breaker. I’ve love to see more videos with her. My daughter would have loved it; now in her 20’s, she’s an 18th c. cook herself as school allows. Charm and charisma aside, I appreciate this shared learning experience. I made 5 “Christmas Puddings” about 20 years ago based upon recipes I found in the old Williamsburg 1930’s cookbook and a British National Trust Pudding book. Totally improvised. I “marinated” the filling in our Massachusetts cold closet (it protruded into the garage and was always less than 40 degrees F). I’m just wondering further as has been discussed about mixing up the ingredients quite awhile in advance? The pudding was delicious and now I can’t recall what I did other than it was loaded with brandy! We had a friend who had spent 20 years in Britain and sang some “Christmas pudding” introduction song as the pudding was brought into the dining room, aflame. Anyone know what that might be?

Mince was still a tradition with the elders in the family while I was growing up in the 70s and 80s. I was one of the few of the younger generation that took to its strong flavors. In some of my studies of more recent recipes, I found a reference to the alcohol helping to break down the texture in the meat to make it less “stringy.” I am now sorry that I didn’t note where I found the information.

Good to know I am not the only one keeping the tradition alive.

Yorkshire Pie sounds a little like “Turducken”. I always thought that was a recent invention.

Loved your article. My grandmother always made mince pie from scratch. It is not clear to me if you use non-rendered or rendered suet. I’d ask her, but she is no longer gracing this earth. Thanks so much!

Thank you for sharing your memories of your grandmother.

Raw suet may lend a “meaty” taste to the dish due to the presence of connective tissue, etc. Rendered suet will provide the moisture and texture, and will more likely not affect the overall taste.

I think you may mean, “In case you’re wondering…” Great….very informative site and subjects. Thanks for your continued efforts!