In my last post, I took a brief look at the important role suet had in 18th century foodways as well as in life in general. I gave an over-simplified explanation that suet is the hard fat from the loins of beef and mutton. I’d like to add a little more meat, so to speak, to that definition.

Beef suet can sometimes be a bit difficult to find here in the United States. I suspect that much of it ends up rendered, mixed with peanut butter and birdfeed, and packaged into blocks of winter-time bird food. Suet is a perfect high-caloric attraction for all my feathered friends who decide to stick out the cold northern winter with me.

I recently stopped at a well-respected butcher’s shop in the area. After my unsuccessful search for suet at five local grocery store meat departments, I was pleased when the butcher trotted out of the cooler with a 10-pound bag of the white stuff. My pleasure turned to disappointment, however, when I opened the bag at home to discover that he had just hoodwinked me with 10 pounds of hard muscle fat. It’s not the same thing.

Real suet is located on the inside of loin area of cattle and sheep. It is the hard fat that surrounds the animal’s kidneys. If you ask your butcher for suet, be sure he or she understands that you want kidney fat.

The difference between hard muscle fat and kidney fat may not be all that apparent up front. They both can be quite stiff and look much alike. The real difference can seen during and following the rendering process.

Suet, as opposed to muscle fat, contains a higher level of a triglyceride known as glyceryl tristearate, otherwise known as stearin. The result is that suet has a higher melting point and congealing point than regular fat.

This little point of trivia is important in order to understand the old English recipes. Suet is grated or picked into small pieces as part of the process of preparing it for cooking. When mixed with other ingredients — let’s say the a batter for a traditional boiled pudding, the particles of suet retain their mass well into the cooking process. When the melting point of suet is finally reached, the surrounding batter has already begun to set. By the time full baking temperature is reached within the pudding, the suet has melted, leaving a void in the batter.

Consequently, the use of suet in such dishes as puddings, dumplings, and mince pie results in a spongy texture. If the lower-melting muscle fat is used in suet’s place, the fat will melt before the batter has a chance to set, resulting in a much heavier final result.

Not only is suet used for textural purposes, but it is also used to add moisture to the dish without adding a strong meaty flavor that is so common with muscle fat. Suet has a much milder flavor.

I went ahead, for experimentation purposes, and rendered some of the muscle fat the butcher passed off to me as suet. Beyond the fact that my entire house smelled for three days like one giant broiled steak, the rendered fat I ended up with resembled a side dish of my grandma’s runny mashed potatoes. But unlike my grandma’s mashed potatoes, my rendered muscle fat never hardened, even when it was cold.

This may seem strange, but I generally keep a couple of gallons of commercially rendered tallow within reach here at the office. I use it to make a couple of products here at Jas. Townsend & Son. “Tallow” is a general term that means rendered fat. Tallow can be made from suet, or muscle fat, or a combination of both. The texture of tallow varies broadly, however, depending on the raw form of fat from which its made. So if you find yourself someday in the reenacting mood to make tallow candles, this is an important bit of information to know. You simply cannot make candles with tallow rendered from muscle fat.

Rendered suet, on the other hand, will congeal into a solid chunk. (I’ll talk about the actually rendering process in my next post.) The chunk I made felt like a bar of beauty soap. Mix rendered suet with a little lye and a chemical reaction occurs that results in water-soluble sodium stearate — the primary ingredient in most hand soaps.

Oh, one other thing: Just like beef muscle fat, pork lard is an unsatisfactory substitute for suet. You may have a difficult time distinguishing by sight between a lump of lard and a lump of suet tallow, but don’t even think about using it as a substitute.

Now in my previous post on 18th century Christmas pies, as well as in the accompanying video, we suggested using vegetable shortening as a suet substitute. Admittedly, it’s not a very good substitute, but it does provide the moisture without adding a strong flavor.

The problem is that while vegetable shortening’s melting point is relatively the same as suet, its congealing point is much lower. What that means is this: when we shot the video, we had to freeze the vegetable shortening in order to grate it. Then we had to keep it frozen until the very last second. But even then, the moment we added the grated vegetable shortening to the other ingredients, it lost its mass and acted like room-temperature butter, coating the other ingredients rather than retaining its particle shape. The final result was still a delicious pie, but it didn’t have the desired spongy texture that would have resulted from using suet.

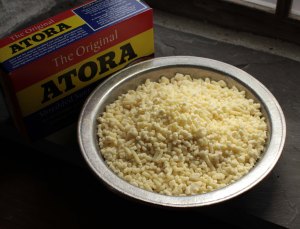

Now, if you live in the U.K., you’re probably wondering why I suggest going through the hassle of dealing with raw suet when all you have to do is stroll down to the corner grocer and pick up a box of processed suet. While I’m sure there are stores here in the States that sell this product, I sure can’t find it here in northern Indiana. We had to go online to buy a box, which ended up going through customs to get here.

If you decide to use this processed product in your 18th century foodie experiments, beware that it uses wheat flour (15% by weight) as a stabilizer to improve its ability to retain its shape. From a historical-accuracy standpoint, the addition of flour may be perfectly legitimate. William Kitchiner, in his 1817 book, “The Cook’s Oracle,” suggests that during hot weather, shredded suet should be dredged with flour — apparently to stabilize its mass retention.

The caveat I offer is that if you are already using flour in your 18th century recipe in addition to that used in processed suet, you may have to make a minor adjustment to the amount of flour in order to get accurate results. Modern recipes that call for suet, by the way, already accommodate this additional flour.

And finally, when shopping for suet, try to get the whitest suet you can find. This little tidbit is reiterated throughout the old cookbooks. Suet tends to turn a buttery yellow as it ages, and as it does, it also takes on a stronger flavor. Most beef offered for sale here in the States is aged. This may pose an additional challenge in finding fresh suet. A processor who actually slaughters the animal is probably your best bet for finding the freshest suet. A light buttery colored yellow suet is still usable, but a clean white suet is preferred. And for goodness sake, don’t accept suet that is brown or massively bloody. That may be fine for the birds, but it’s unsuitable for cooking.

In my next post, I’ll examine more closely how to process suet for use in cooking.

I found a please where to buy suet in the us on line try http://www.grasslandbeef.com/Detail.bok?no=670 there in Montana I think. hope this helps

I just bought this – thanks for the post. While it is advertised as beef suet, the actual packaging stated it was ground beef fat. Sooo, petrified I would end up with a nasty Christmas pudding I e-mailed them to confirm it was Kidney fat and this was their response: ‘A good percentage of the suet is kidney fat, but suet includes other fat removed during the break of the carcass into subprimals. The fat can be trimmed from all areas (such as kidneys, loins and abdomen), but the highest percentage is the organ fats.’ They were excellent on a customer service (quick response and said could credit if it was not suitable). I am going to give it a go in Eliza Acton’s Christmas pudding from 1845 and hope for the best. The customer service person said that most of their customers buy this product for Christmas pudding or to make their own sausages and have had no problems. It comes chopped and frozen so I chopped it by hand into smaller pieces and took out anything that wasn’t pure white with a satin texture. . As a Brit, I am excited to see how this will turn out. So lucky I found this site as I almost wasted a tonne of fruit on the pork fat that the Safeway butcher called Suet. Fingers crossed!

John and Cherry, thank you both for the info on Grassland; I’m going to try their suet.

I live in a big city (Chicago) with loads of butcher shops, but I couldn’t find a one that carried suet or even knew what it was. Can you imagine?

Just an update on my November 2013 post regarding Grassland beef suet. I prepared Eliza Acton’s recipe for Christmas pudding from 1845 in November 2013 and I used http://www.grasslandbeef.com suet. If you Google the recipe, you will find it is very heavy on the suet! As noted in my post above, Grasslands/US wellness meats suet is mainly kidney fat, but not 100%. I have to say that the pudding result was very good and there was certainly no ‘meaty’ undertones to the pudding. Therefore, I’d be happy to recommend this to anyone in the USA looking for an almost authentic suet for a Christmas pudding. I do however have a crazy amount of the fat in the freezer as the smallest bag was huge! Best of luck with your puddings.

Oddly, I live in Hawaii. One can get suet at the grocery store! They all seem to stock it.

PS clarification, not odd that I live in Hawaii…

🙂 I love that PS.

I was taught tallow was differant from fat, being waxy and harder in texture. Only comes from one spot in the animal, true suet perhaps? PS- really love this blog!

Hi Bruce. Thank you for your kind words! Yes, you’re correct. The traditional primary definition IS suet (i.e., kidney fat); the secondary definition is that which is rendered from suet. A tertiary definition is any of various fatty substances (and that’s just the noun form of the word). So it’s no wonder there’s some confusion out there. The gallon of commercially prepared “tallow” that sits on my desk that I mentioned in this post can be squeezed from its plastic jug at room temperature — a telltale sign it came from muscle fat and not suet; yet it was labeled “100% tallow” — and technically, I suppose, rightly so. I would, however, be unable to achieve the same results in cooking and candle and soap making with this “tallow” as I would with rendered suet tallow. And that’s the long way ’round explaining why I made the distinction. Thanks again!

Pingback: A Pork Pie with a Standing Crust | Savoring the Past

Pingback: 18th Century Pasties, Part One | Savoring the Past

Thank you so much for the explanation. Now I understand why my one attempt to make pemmican failed so miserably. I had ignorantly used rendered muscle fat (from hamburger). Time to try again with actual suet.

Happy snacking!

Pingback: Please Bring Back the Puddings! | Savoring the Past

Excellent explanation, thank you! I do render my own beef fat for tallow, and keep the leaf lard separate when rendering our pig fat for lard. My tallow , from my grass-fed only cows which does make a difference, is very hard and firm though, but I will separate out the different fats in the future. I’m making a tallow salve, usually with cow tallow, from kidney fat from our sheep, and am curious if there is a difference. Love your blog! 🙂

Thank you! I’ve wondered myself whether there was a significant distinction between beef suet and lamb suet. I have found one or two references in the older cookbooks that suggested that sheep suet has a slightly milder taste, however, the two fats were considered interchangeable by many other authors. It seems the distinction was considered by most to be insignificant. From a more technical standpoint, according to Jennifer McLagan in her 2008 cookbook, Fat, lamb suet is slightly lower in percentages of saturated and monounsaturated fats than beef suet: 47% Saturated and 40% Monounsaturated versus beef’s 50% and 42%. As an aside, the saturated fats in both beef and lamb suet, according to McLagan, consist primarily of stearic and palmitic acids, which are believed to lower LDL cholesterol. Futhermore, your grass-fed animals develop higher levels of Omega-3 and conjugated linoleic acids, both believed to be beneficial to our health.

I raise rare Milking Devon cattle on grass and vegetables and hay without grain or soy or urea or by-products whatever. I’ve made several large batches of tallow and use it for all of my cooking, I’ve been learning about soap-making.

I have rendered the leaf (kidney) fat immediately after slaughter – and I have rendered the additional trimmings that the butcher removes after 21 to 30 days of dry-aging (42*F). It is easier to get a clean cook with the limited blood vessels and meat scraps in the leaf fat, and I think it has less odor. Generally the fat from the second harvesting has a mild odor that reminds me of deep-fat frying.

Some breeds of cattle (Jersey is one) naturally have yellow fat. The Devon fat is a creamy color.

High temperature cooking (frying burgers for example) can cause some chemical break-down of the fat, The process to clean cooking fats to make soap is quite extensive.

Mutton tallow melts at a higher temperature than beef tallow and makes a more brittle soap bar, but is preferred for candles. I think mutton fat has a higher percentage of oleic acid but cannot find a reference at this time.

I don’t care for the smell of mutton tallow, but I don’t like the taste of lamb either. Deer or goat fat should have similar properties to the sheep.

For folks in the NYC area, Grazin’ Angus sells beef suet at the Union Square and Carroll Gardens Greenmarkets. I get it all the time for deep frying. I haven’t tried using it for pastries (leaf lard and butter is my go-to for that) but reading about its properties makes me want to try it in my next pie crust or baking soda biscuits! http://www.grazinangusacres.com/

Pingback: Mutton Tallow Face Salve | grassfood.

Pingback: an adventure in suet | Banny's Pantry

Thank so much for this info! Your explanation was so complete – answered all my questions. I was searching for a traditional mincemeat recipe & realized I didn’t know what suet actually was. Thanks, too, for your caveats re: buying true suet. BTW, I love that your hobby is recreating all these traditional products/methods. I look forward to reading your other posts.

Hi,

Have you ever heard of or tried suet pudding? I remember my mother would make it for my sister on her birthday because it was one of her favorites. To me, it was just a hunk of fat with a sugar syrup poured over it and made my fillings rattle when I ate it!

My current project is perfecting the diner burger, which so far has been unatainable. I thinking of adding some beef suet to the freshly ground chuck to bring the fat content to 30%, but I’m a little concerned about the shelf life and wonder if tallow would be a better alternative or a big mistake.

Most of my traditional pudding experiences have been with 18th century recipes, of which the majority call for suet, grated bread crumb, and other ingredients. Boiled and steamed puddings of the 19th century — especially those in American cookbooks — seemed to have tilted more toward flour instead of bread crumb. Recipes from the latter half of the 19th century also included chemical leavenings. I’ve had little experience with this type of pudding, but equipped with a good sauce, I’m game for nearly anything. Here’s a good example of some late 19th century suet puddings that may be similar to those to remember: https://books.google.com/books?id=KBcEAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA85&dq=suet+pudding&hl=en&sa=X&ei=YszSVIOaEcyYgwS594G4DA&ved=0CEoQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=suet%20pudding&f=false

As far as augmenting your ground beef with suet, I suspect it’s a brilliant idea. You’re correct to be concerned about the shelf life of raw suet. I recently ran across a company that freeze-packs fresh suet: http://www.massanaturalmeats.com/beef-suet-kidney-fat/

Suet that has been rendered into tallow, if done properly, has a very long shelf life. fatworks.com offers rendered suet in 14.8-oz. jars. It’s the real stuff and a quality product. I used some just this morning to make a oxford pudding. It may be a viable option for what you’re wanting to do. We plan to offer this product as well on our website, jas-townsend.com in the near future.

I wish you success in your pursuit!

Kevin,

Thanks for a very informative reply!

I’m liking the frozen suet idea as I would never cook enough bugers to use it all at once and would wind up throwing most of it out.

A couple of months ago, I was at my brother-in-law’s vacation home in Florida, we bought some ground pork to make burgers and the butcher was kind enough to give me some pork fat. I didn’t have a meat grinder so I cut the fat into small pieces and mixed it in with the ground pork. We cooked the burgers on the grill and what a difference! They were so moist and flavorful.

Hi, I think my question is answered but would like confirmation I got it right please?

I bought some beef tallow, the ingredients say it is grass fed beef suet. The brand is Cradoc Hill in Tasmania, Australia. I presume I can use this in place of regular suet for a traditional plum pudding? Please advise. Thanks, Carla

I’m unfamiliar with this product, but a simple test would be if this tallow is solid at room temperature. If it is, it’s perfect for puddings.

Pingback: Suet - Ten Random Facts

Thank you…this was most helpful. I recently purchased a recipe book

of old recipes, from Silver Plume, Colorado with many calling for suet. I had no clue what that was. So, thank you very much. I will now attempt to make some of these delicious sounding dishes and pies. God bless you!

In Australia you can buy suet and lard in the supermarket. A good butcher will also supply the fat so that you can render your own, although you may need to order a couple of days in advance to get the quantity you want. Last week my local butcher supplied me with half a kilo of fat cut from an aged, dry-hung side of beef and it rendered beautifully making a creamy white, sold block. Similarly any Asian butcher will supply pork fat, usually back fat but if you order in advance, leaf fat for rendering lard. If you don’t use either suet or lard very often it is worth th trouble to render it yourself. It may be more expensive relatively speaking in terms of labour and raw ingredients, than buying the processed supermarket product but if oyu make it yourself you know exactly what goes into it.

All good info, but this is somewhat new territory for me. I want to make a batch of mincemeat and the recipes call for suet. I do not want to mess it up by accidentally using an incorrect fat. I have a block of tallow I acquired from a local pasture raised cow (of some sort) and the tallow is solid at room temp, beautifully white and grates nicely. I THINK it is what I want for the mincemeat. If you are inclined to give me a nod of agreement or disagreement it would be appreciated.

Wow, I’m sorry for the delay in my response. In its raw form, it can be hard to tell. Raw Suet is often filled with very thin membranes. It’s for that reason that pork suet is called leaf fat because of how the fat can be broken apart due to the membranes. Hard muscle fat, however, does not have this membrane network in it. Both hard muscle fat and raw suet will be solid at room temperature. It’s not until the fat is rendered that the real difference is noticeable. One word of advice when purchasing suet is to ask specifically for kidney fat.

Thank you for the input although I don’t think my question was worded thoroughly. It is rendered tallow. I made the mincemeat with the tallow – it grated beautifully – and it turned out fine. My first ever effort of course. It was a bit bland as I prefer a tangy mincemeat with more high notes but it is aging well. Made fine pie in spite of it’s delicate nature. I think I need to learn a lot more about natural fats and their uses. We rendered heirloom field raised pork fat and got lovely pastry lard so that is my starting point. No need to reply unless you just want to. I appreciate your input!

After watching the video we went to our local butcher and got a lovely 2+ pound chuck of suet. It was the real material from a cow slaughtered that very day. We got it home and next day cut it up and cleaned out the bits as much as we could and broke it down and popped it in the slow cooker on low at first and then to warm once it started to bubble (we translated bubbling as ‘cooking’ and we didn’t want to cook it). And it warmed and warmed and warmed.

Now, I’ll tell you, we warned it a while. I kept watching it and eventually it got down to a lot of liquid with about a third of it being pearlescent little nodules. However I’d been warming it for twelve hours and it was late and I was tired so I poured it through a cloth covered sieve into a bowl. Now, what I rendered was a beautiful buttery yellow colored liquid. Really a gorgeous looking material. I scooped/poured this into individual portions to let it harden. I was left with a cloth full of stuff (I did squeeze it a few times to ‘wring out’ any extra liquid).

By morning the liquid had hardened to the soft wax consistency described as suet. I’m pretty impressed.

Here are a couple of thoughts:

1. Chop that suet SMALL. Seriously, once you’ve picked it, chop it as fine as you can. Our suet was rendered down to about two thirds fine, one third chunky (say 1/4″ chunks and the occasional 1/2″ chunk), my advice is make sure its ALL finely chopped up. After I ‘reviewed’ our leftovers in the cloth it was clear that there was some suet still in those lees. Perhaps as much as half but probably not. But as I said, it was late, i was tired, etc. The finer it is, I’m guessing, the quicker it will render down to liquid. That said, I still got about 1.5 pounds rendered from 2.5 pounds of suet bought from the butcher. I haven’t taken an exact weight yet (see question 1 below).

2. Don’t be fooled by stuff floating around in the rendered suet, once you strain it, you get a beautiful product. I looks pretty dirty until you strain it but once you do it is a thing of beauty.

And a couple of questions:

1. I learned I have no idea how to get the suet out of the molds without demolishing them somewhat. Any thoughts on how to ‘release’ the suet from the mold? I used small clear glass bowls (about half cup sized). Can I heat them? Can I cool them? Seriously, any advice would be great. The one we ‘sprung’ from its confinement had some rough edges from prying it out. I’m sure there is an easier way.

2. The centers were a little harder than the edges on the mold we sprung. That was after about 14 hours. I’m guessing that was partly because of the temperature in our kitchen, but does it take a full 24 hours or so for the suet to harden? Any thoughts would be appreciated.

Last, thanks for the idea, we love the videos and we made the suet so we can make some puddings!! [And I’m trying to talk the wife into letting me buy a candle mold!]

As an update, we put one of the molds in the fridge and it released with with just a nudge after a few hours. This also solved the soft edges problem. So cool suet releases more easily. Not a rocket science but good to know. 🙂

Thanks for sharing this! Yes, that makes sense, the suet should shrink, if ever so slightly, as it cools. I hope you enjoy your puddings. Don’t forget the sauce!!!

I am very interested to know about other properties for health that kidney fat has. It is a key ingredient in Mesopotamian medications – the best is fat of the left kidney of a castrated sheep, as castration increases the amount of fat- and why God chose that to be offered on the altar in Jerusalem’s Temple, with a prohibition of eating it. This is part of an MA thesis and I welcome comments please!

Excellent to know! Thank you!

I realize this post is from quite a while ago, but hopefully you’re still around. You mentioned that as soon as you open the bag you could tell that what you had bought was not suet, but muscle fat. How are you able to tell? Is it the texture? The smell?